Are AI Chip "Useful Lives" Creating Useless Earnings?

Michael Burry's depreciation warning, hyperscaler AI CapEx, and the cash reality at Alphabet and Amazon

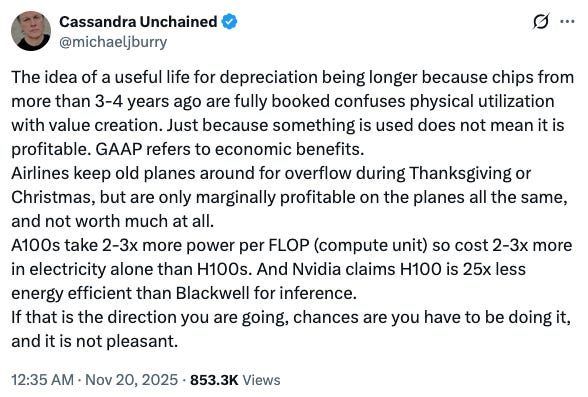

Michael Burry, the institutional investor immortalized in The Big Short, has broken his silence on AI. In a tweet on November 11, 2025, he didn’t just suggest the AI trade is a bubble, he accused the hyperscalers of accounting manipulation.

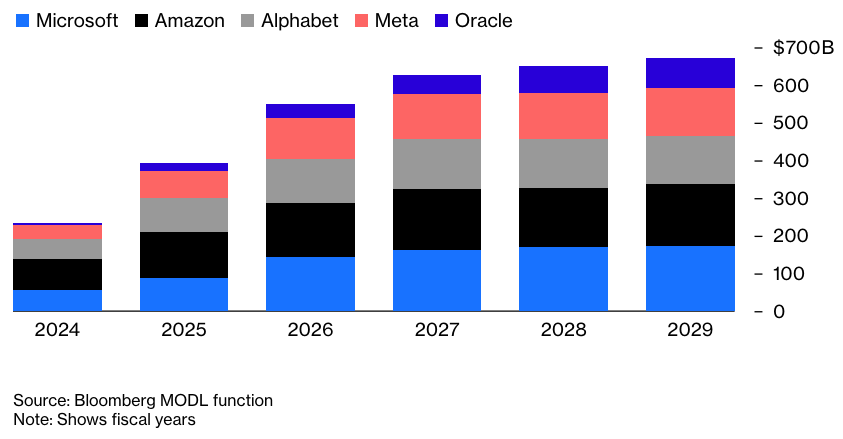

His claim: Alphabet (GOOGL 0.00%↑), Amazon.com (AMZN 0.00%↑), Meta (META 0.00%↑), Microsoft (MSFT 0.00%↑), Oracle (ORCL 0.00%↑) are simultaneously ramping AI CapEx and stretching the “useful life” of their NVIDIA-powered data center hardware. In his numbers, that could understate depreciation by roughly $176 billion between 2026 and 2028 and leave reported operating income at companies like Oracle and Meta more than 20% above what he sees as economic reality.

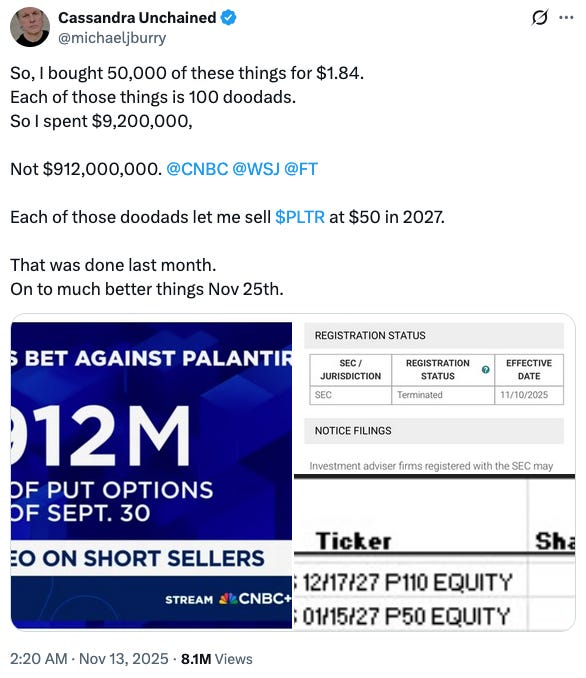

Burry has backed this view with put options on NVIDIA (NVDA 0.00%↑) and Palantir (PLTR 0.00%↑), the poster children of the AI boom, and doubled down after NVIDIA’s Q3 2025 earnings, arguing that investors are confusing “physical utilization” of older GPUs with true economic useful life. Rather than shorting the hyperscalers directly, he’s made a capped-downside, leveraged bet1 against the most sentiment-driven beneficiaries of the AI boom: the chip vendor at the center of the hyperscalers’ CapEx mega-cycle and a highly-valued pure-play AI software name.

If the economics or depreciation assumptions crack, hyperscalers can slow CapEx and watch free cash flow surge. NVIDIA and Palantir can’t: NVIDIA’s growth is tied to GPU budgets, and Palantir trades at a sky-high 223x TTM P/FCF. Burry’s trade is a focused bet against AI euphoria, not against the diversified cash machines like Alphabet, Amazon and Microsoft.

If you own those hyperscalers, as I do, you can’t dismiss this as cranky tweeting. You need to understand the accounting, what’s a genuine concern, and what’s mostly optics.

GAAP Depreciation, Accrual vs Cash, and Where CapEx Really Bites

To understand Burry’s accusation, we need to revisit the difference between cash and accrual accounting in the context of AI chips and servers. In earlier articles I walked through how depreciation and other non-cash items flow through the financial statements.

Suppose Google spends $900,000 on GPU racks this year:

Cash reality (cash flow statement): the full $900k leaves the bank today and shows up as CapEx under Investments In Property, Plant & Equipment.

Accrual / GAAP reality (income statement): you don’t expense $900k immediately. Management estimates a useful life, say 3 years, and spreads the cost evenly: $300k of depreciation each year as Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) or Selling, General, and Administrative (SG&A).

Economically, it’s one big cash hit upfront. In accounting terms, that hit is smoothed over several years as depreciation, so operating income (EBIT) shows a steady annual expense rather than a single lump. On the balance sheet, the GPUs sit in Property, Plant & Equipment (PP&E) and are gradually reduced by accumulated depreciation.

Depreciation is a non-cash charge: it lowers operating income and PP&E, but gets added back in operating cash flow because the cash already left when the CapEx was made. That’s why:

Operating Cash Flow (OCF) = Net Income + Depreciation (and other non-cash charges) ± Working Capital

Free Cash Flow (FCF) = OCF - CapEx

Now tweak just one assumption, useful life, and the optics change dramatically. Using the same $900k:

If you depreciate over 3 years → $300k per year hits the income statement.

If you depreciate over 6 years → only $150k per year hits earnings.

Same cash out, same hardware, but under a 6-year schedule, GAAP operating income looks much higher in the early years. That tension is exactly what Burry is attacking.

What Hyperscalers Have Actually Done With Depreciation

Across the industry, server lives have drifted out from roughly 3-4 years to 5-6 years just as AI CapEx has exploded.

In early 2023, Alphabet extended the useful life of its servers from 4 to 6 years, and certain network equipment from 5 to 6 years, cutting its 2023 depreciation by $3.9 billion and boosting earnings by $3 billion. Its investor FAQ adds that depreciation lives are “regularly evaluate[d] for factors such as technological obsolescence and our planned use and utilization”, reinforcing the idea that this is meant to track economics, not just massage optics.

Amazon has twice lengthened, and then partially shortened, the lives of AWS servers and networking kit. A Q4 2022 change from 4 to 5 years for servers (and 5 to 6 for networking) reduced 2022 depreciation by $3.6 billion, and lowered net loss. In Q4 2023, Amazon went from 5 to 6 years for servers, adding an expected $3.1 billion to 2024 operating income. Then, in Q1 2025, it shortened the life of a subset of servers from 6 back to 5 years, citing the “increased pace of technology development, particularly in the area of artificial intelligence and machine learning”.

Meta has moved from 3 years in 2020 to 5.5 years by 2025 through a sequence of extensions.

The pattern is clear: an industry that once assumed 3-4-year refresh cycles now depreciates much of its fleet over 5-6 years. That matters when the numbers are this big: Alphabet is expected to spend over $90 billion on CapEx in 2025 and Amazon more than $125 billion, with most of it going into AI infrastructure. Under 5-6-year schedules, only a slice of that shows up as depreciation each year.

Burry’s Case: The CapEx Hyper-Cycle and Earnings Mirage

Burry’s argument is that AI hardware really lives 2-3 years, but is being treated as if it lives 5-6. NVIDIA’s flagship GPUs are on a 3-year cycle, with each generation 2-3x more efficient per unit of compute and per watt, so keeping old chips in service quickly becomes uneconomic for state-of-the-art training. Yet just as hyperscalers ramp CapEx to unprecedented levels, they’ve lengthened depreciation schedules to 5-6 years, which mechanically flatters earnings. Burry estimates that from 2026-2028, depreciation will be understated by about $176 billion, causing hyperscalers to overstate profits by more than 20%. If the true economic life is closer to 3 years, a cliff eventually arrives: either via large impairments when “stranded” chips are written down, or via the realization that what is considered growth CapEx is actually permanent sustaining CapEx, locking these companies into structurally lower free cash flow.

Bloomberg, summarizing this concern, has warned that hyperscalers could collectively spend trillions of dollars on AI infrastructure over this decade, with the risk that hardware lifespans prove shorter than the 5-6 years management currently assumes.

In that scenario, earnings quality deteriorates and valuations reset: optimistic useful lives + explosive CapEx + high multiples = vulnerable earnings and fragile sentiment.

The Bull Case: Longer-Lived Chips, Smarter Data Centers, and “CapEx Now, FCF Later”

The bullish view starts from a different premise: AI hardware and data center economics really have improved, and the accounting is trying to catch up rather than inventing a story.

Hyperscalers and NVIDIA argue that GPUs don’t drop dead after three years. The typical pattern is:

Years 1-3: frontier-model training on the latest chips.

Later years: those same GPUs are repurposed for inference (serving already-trained models to users), smaller models and internal workloads.

During NVIDIA’s Q3 FY2026 earnings call, CFO Colette Kress said that “thanks to CUDA [the software stack], the A100 GPUs we shipped 6 years ago are still running at full utilization today, powered by vastly improved software stack”, and emphasized that “GPU installed base, both new and previous generations, including Blackwell, Hopper and Ampere is fully utilized”. At an a16z infrastructure event in late October 2025, Google’s VP and GM of AI & Infrastructure, Amin Vahdat, said their 7-8-year-old TPUs are still running at 100% utilization. Peak use may be 2-3 years, but economic use can be much longer.

Engineering also helps the case for longer lives: modern data centers are modular (you swap GPUs and networking rather than ripping out racks), cooling and power management are better, and performance gains per generation are moderating, with more of the improvement coming from software and systems optimization. During Microsoft’s Q1 FY2026 earnings call, CFO Amy Hood has stressed that assumed lifetimes on some “short-lived assets” are matched to multi-year cloud and AI contracts - the revenue is designed to cover the hardware over its GAAP life.

On this view, today’s “CapEx now, free cash flow later” story is credible. Operating cash flows at Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft and Meta keep climbing, while management is reinvesting heavily in AI infrastructure because they see more demand than they can meet at attractive returns. Even if FCF margins settle lower than in the ultra-lean 2010s, absolute FCF can still be much larger on a far bigger revenue base. And, crucially, if returns disappoint, hyperscalers can pull the CapEx lever; the real pain would then fall on the supply side - GPU vendors and leveraged data center operators whose growth depends on the spending hydrant staying on full blast.

Burry’s Rebuttal: Utilization ≠ Value Creation

Burry’s response, which I think is intellectually fair, is that just because GPUs are busy doesn’t mean they’re economically productive. Older chips can be far less power-efficient, so once you factor in electricity, cooling and the opportunity cost of not deploying newer hardware, they may only be marginally profitable. GAAP “useful life”, he argues, is supposed to reflect the period over which an asset generates real economic benefits, not simply the time until it physically stops working or can be assigned some low-value task.

In that sense, Burry and NVIDIA’s CFO are almost talking past each other: NVIDIA is saying, in effect, “our chips don’t become landfill after three years; customers keep them busy”, while Burry’s question is, “yes, but are they earning enough incremental return, net of power and opportunity cost, to justify spreading their cost over six years?”. Both perspectives matter if we care about the true economics behind today’s AI earnings.

In-House AI Chips: Eroding (Slowly) the NVIDIA Dependency

Parallel to the NVIDIA GPU boom is a quieter story: the rise of in-house AI chips at the hyperscalers. GPUs remain the “Swiss army knife” of AI, but Google, Amazon and Microsoft are building custom ASICs (Application-Specific Integrated Circuits) to handle an increasing share of their AI workloads.

Google led with TPUs (Tensor Processing Units) in 2015, and is now on its seventh generation (Ironwood). Amazon followed with Inferentia (for inference) and Trainium (for training), now in its third generation; Anthropic is training on half a million Trainium2 chips in an AWS data center with no NVIDIA GPUs. AWS says Trainium delivers 30-40% better price-performance than “other hardware vendors” on its platform. Microsoft is pursuing a similar path with its Maia accelerators for Azure.

The logic is straightforward: custom ASICs are expensive to design, but at hyperscale they can lower unit costs, improve energy efficiency and give more control over the AI stack. NVIDIA GPUs remain the flexible, high-end workhorses; TPUs, Trainium and Maia are more like specialized power tools. Over time, a larger share of AI training and inference can run on these in-house chips, reducing the need to buy NVIDIA for every incremental workload and putting at least a partial lid on the AI CapEx bill.

How This Shows Up In the Numbers: Earnings vs. Free Cash Flow

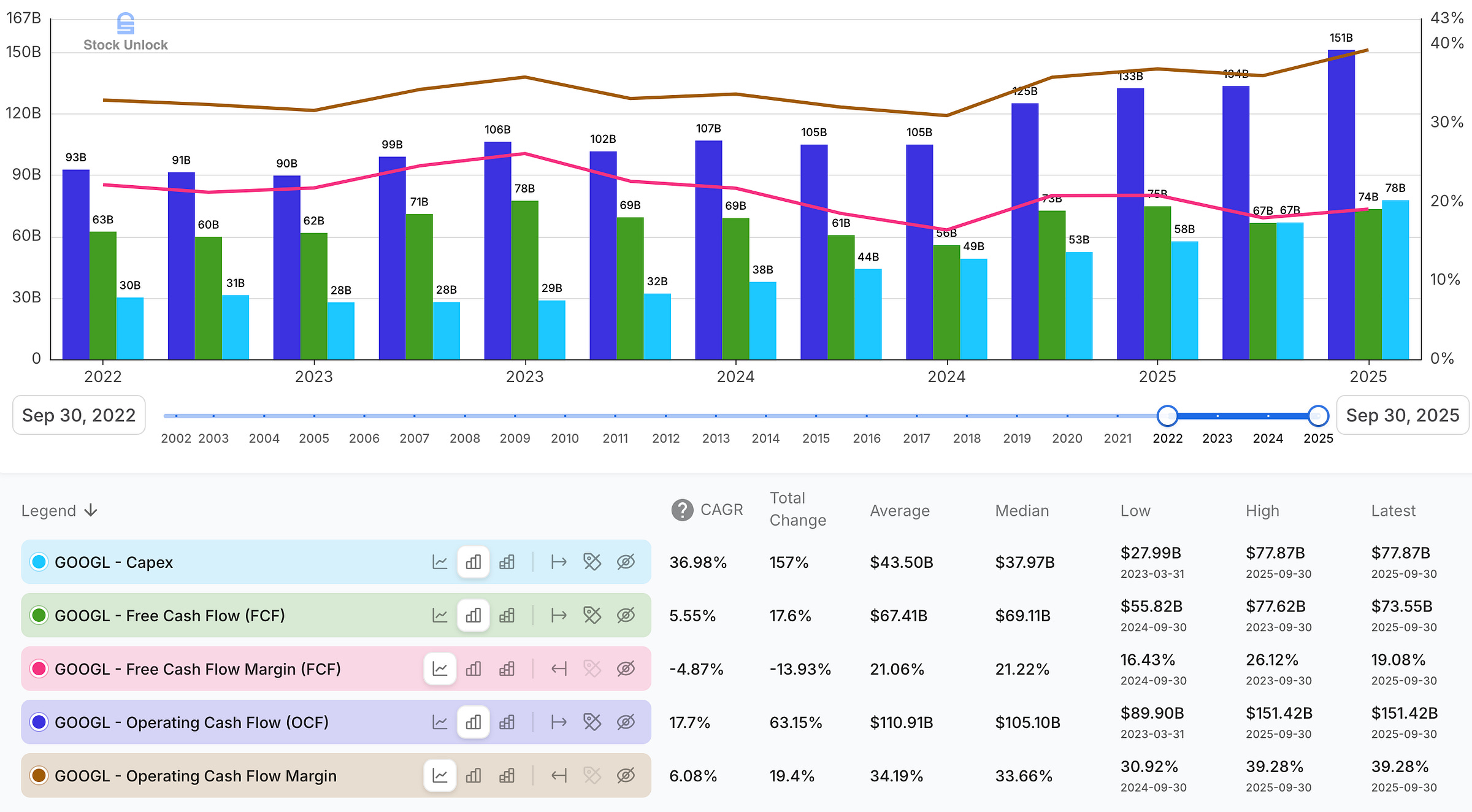

You can see this tension clearly in the financials of Alphabet and Amazon.

Since the AI boom in late 2022, Google’s operating cash flow has climbed strongly at 17.7% CAGR to $151 billion on a trailing basis in Q3 2025, reflecting the underlying profitability of Search, YouTube, Cloud, etc. but free cash flow has grown slowly at 5.6% CAGR, because CapEx has exploded for AI data centers at 37% CAGR. While Google’s OCF margin has expanded from 33% in 2022 to 39% in late 2025, FCF margin has shrunk from 22% to 19%, as the company ploughs more of its operating cash back into infrastructure.

On an earnings basis (which benefits from extended depreciation), Alphabet trades at a low-30s multiple of net income. On a free cash flow basis (which reflects the full CapEx burden), the implied multiple is in the low-50s.

A similar pattern exists at Amazon. Over the same 3-year period, Amazon’s operating cash flow has surged at a 49% CAGR to $131 billion on a trailing basis in Q3 2025, and its OCF margin has expanded from 8% in 2022 to 19% in Q3 2025. Yet free cash flow sits at only $11 billion, implying an FCF margin of roughly 1.5% and a valuation around 230x FCF, even though its P/E in the low-30s doesn’t look extreme for a dominant aggregator.

Some of this simply reflects aggressive growth investment where management believes returns are high, but Burry’s point is that the widening gap between net income and cash is being flattered by depreciation assumptions.

Are Useful Lives Too Long?

My view is that it’s a judgment call, not outright cooked books (so far): Extending server lives from 3 to 4 years as data center design improves and workloads diversify is plausible. Stretching all the way to 5-6 years for rapidly advancing AI accelerators is more debatable, especially given effective economic life shrinking for leading-edge GPUs as upgrades accelerate. However, the changes have been fully disclosed, and so far there is no hard evidence (whistleblowers, enforcement actions, restatements) that this is a deliberate deception rather than aggressive optimism.

The bigger issue is structural CapEx intensity: Even if the useful life assumptions prove roughly right, AI is turning hyperscalers into more capital-intensive businesses than they were in the 2010s. Sustaining CapEx (the amount needed to maintain current performance) is likely to be higher going forward, leaving structurally lower FCF margins than the peak years of the ad/cloud/commerce boom.

If Burry is directionally right, the pain hits vendors and the marginal players first. If hyperscalers decide their returns on AI CapEx are lower than expected, they retain flexibility to moderate CapEx.

What This Means for Alphabet & Amazon in My Portfolio

For my own positions in Alphabet and Amazon, the accounting lives matter less than the basic question of cash in vs cash out: are these incremental AI dollars actually driving faster revenue growth (Search, Cloud, Ads, Prime and so on), widening moats through better products and stickier platforms, and growing operating cash flow faster than CapEx over a full cycle?

If the hyperscalers’ CapEx mega-cycle brings in strong 20-30% returns on invested capital (ROIC), rising operating cash flows and a credible path to stabilizing free cash flow margins in the 20s, I’m prepared to view them as more capital-intensive compounding machines than they used to be. That requires separating earnings optics from economic reality: As discussed earlier, Alphabet and Amazon look much cheaper on EPS than on FCF, so I anchor on OCF growth and CapEx discipline, not headline earnings.

Over the next few years, I’ll be watching three things very closely:

Useful lives vs reality: do Alphabet and Amazon start taking impairments on AI hardware or shorten useful lives again, especially for accelerators?

CapEx vs cash generation: does CapEx growth eventually slow while FCF accelerates, or do we end up on a permanent AI CapEx treadmill?

External pressure: do regulators or auditors begin publicly questioning useful life assumptions?

If those signals turn negative while the narrative stays euphoric, that’s my cue to reassess.

Final Thoughts

Burry is not always right, but he is almost never trivial. His AI short is not a lazy “bubble” call; it’s a very specific claim that earnings at the core of the AI boom are being flattered by optimistic depreciation and an AI CapEx spree that may prove more sustaining than growth. At a minimum, that should force any level-headed investor in Alphabet, Amazon or Microsoft to look past the headline EPS and ask: what is the real economic life of this hardware, and what does that imply for future free cash flow?

At the same time, the hyperscalers are not blind. They are running formal life-studies, adjusting assumptions (including shortening useful lives again when AI advances faster than expected), investing heavily in their own chips, backed by management commentary that AI and cloud demand remains very strong. The cash flow statements show robust, growing operating cash flows and management teams that have already earned the benefit of the doubt on big, long-duration bets.

Where I land today is simple: I take Burry’s warning seriously, but I don’t view it as a reason to abandon high-quality compounding machines whose economics I still like. It’s a reminder to anchor on cash flows and returns on incremental CapEx. If AI CapEx delivers high, durable returns, today’s accounting noise will fade into the background; if it doesn’t, the cracks will show up first in cash, not in carefully manicured income statements.

As an investor, my task is to watch the numbers, monitor what management does more than what it says, and be ready to change my mind if the cash stops showing up.

Burry has spent about $9.2 million buying 50,000 long-dated put option contracts on Palantir (PLTR 0.00%↑), each giving him the right to sell 100 shares at $50 sometime before 2027. In other words, he’s built a highly leveraged, time-bounded bearish bet that Palantir’s share price will be well below $50 by then, without shorting the stock outright. His maximum loss is the $9.2 million premium if Palantir finishes above $50, but the payoff becomes huge if the stock falls sharply. Importantly, this is a valuation and hype call more than a bankruptcy call: he is using one of the most richly valued AI winners as the vehicle to express his broader skepticism that AI-linked earnings - flattered, in his view, by optimistic depreciation and a CapEx hyper-cycle - are being priced far too generously by the market.