When Growth Runs on Debt: The CoreWeave Case Study

A deep dive into the leverage, depreciation, and synthetic demand powering the AI neocloud boom

In today’s market, few sectors are hotter than AI infrastructure. The meteoric rise of AI data center operators like CoreWeave (CRWV 0.00%↑) has captured the imagination of many investors, with share prices soaring and bold projections flying across social media. A narrative has emerged: these companies are must-own, no-brainer plays on the AI revolution, backed by demand from hyperscalers like Microsoft, and Google.

I’m offering a fundamental perspective here: I don’t own CoreWeave (or any of the so called neoclouds), and as a value investor I care about understanding what I’m buying and the dynamics of the industries I invest in, not chasing momentum.

After studying the S-1 filing1, the financing structures, and the synthetic demand loops, my takeaway is sober: CoreWeave is highly speculative, and its model (heavy leverage, concentrated customers, fast-aging assets) raises red flags that deserve scrutiny from anyone considering the stock.

The Bull Case: Explosive Growth, Hyperscaler Demand, and Its Hidden Risk

Hyperscalers like Microsoft, Google, and Amazon face acute compute shortages, opening the door for data center operators such as CoreWeave to rent GPU capacity and act as “shadow clouds” for AI workloads. This outsourcing model has produced staggering top-line growth across neoclouds, but much of that demand is really a transfer of balance-sheet risk: hyperscalers expand capacity without tying up their own capital, while debt-financed neoclouds assume the depreciation, interest costs, and refinancing pressure. Great for Big Tech’s CapEx optics; capital-intensive and fragile for the neoclouds.

Why It’s Risky, in One Glance

Negative cash generation: H1 2025 operating cash flow was negative; debt service was funded largely by new borrowings and IPO proceeds, not operations.

Refinancing wall: $986 million due in 2025 and $4.2 billion in 2026 must be refinanced or repaid, likely at high rates.

Shrinking collateral: Loans are secured by GPUs that depreciate quickly as new NVIDIA chips launch; principal stays fixed while collateral value falls.

Covenant exposure: Must meet leverage and contracted-revenue tests; a miss can trigger paydowns or tighter terms.

Customer concentration: Microsoft was 62% of 2024 revenue (Q2 2025’s Customer A, 71%). Any pullback risks breaches right as collateral ages.

Ongoing external funding: Management says growth needs more debt/equity, meaning higher interest costs or shareholders’ dilution.

From Crypto to Cloud: CoreWeave’s Reinvention

Founded in 2017 as a crypto miner under the name Atlantic Crypto, CoreWeave pivoted to GPU rentals and then to cloud compute for AI. After generative AI took off in late 2022, it landed major contracts with Microsoft and OpenAI.

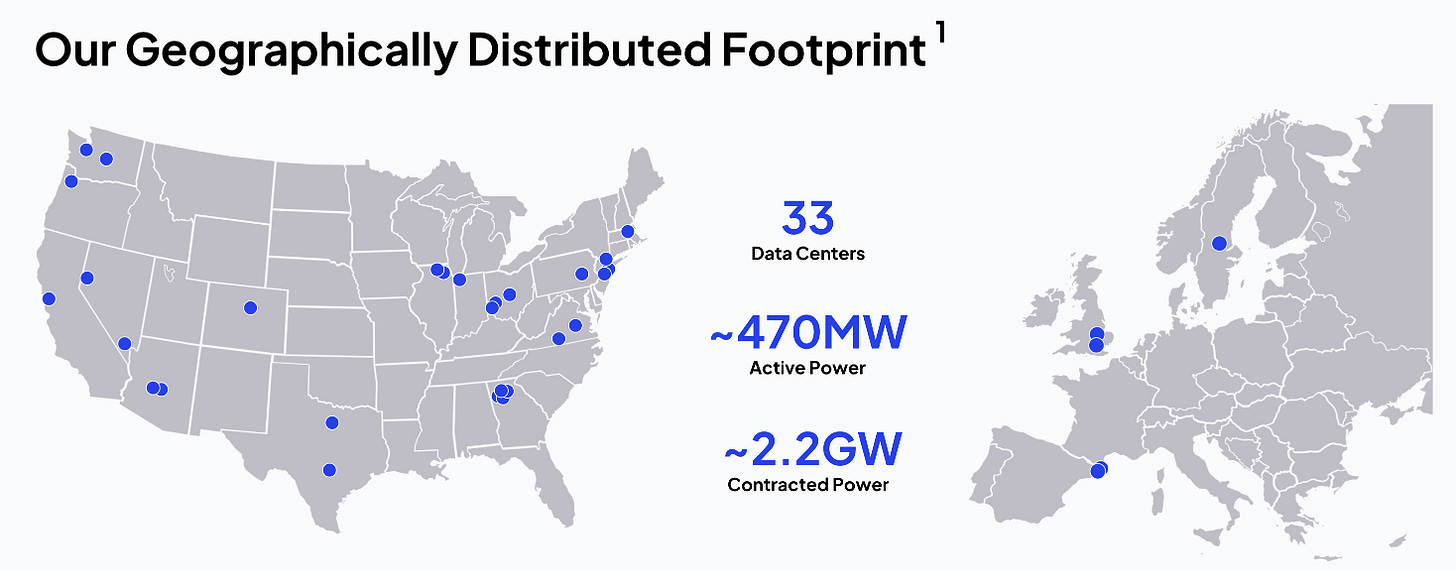

Today, it reports 250,000+ NVIDIA GPUs across 33 data centers with 470MW of active power - among the largest GPU fleets outside AWS, Azure, and GCP.

They’ve been dubbed “the multibillion-dollar backbone of the AI boom” by Wired, but backbones don’t usually run on floating-rate debt, negative operating cash flow, and a single customer supplying most of the revenue.

Financials: Rapid Growth, Rising Losses

When CoreWeave filed its S-1 filing earlier this year (targeting $35 billion IPO valuation), it warned:

“Our operations require substantial capital expenditures, and we will require additional capital to fund our business and support our growth […]”

The filing also disclosed material weaknesses in internal controls and extreme customer concentration.

Key numbers:

2024: $1.9 billion revenue; GAAP operating income $324 (17% margin) and GAAP net loss $863.4 million.

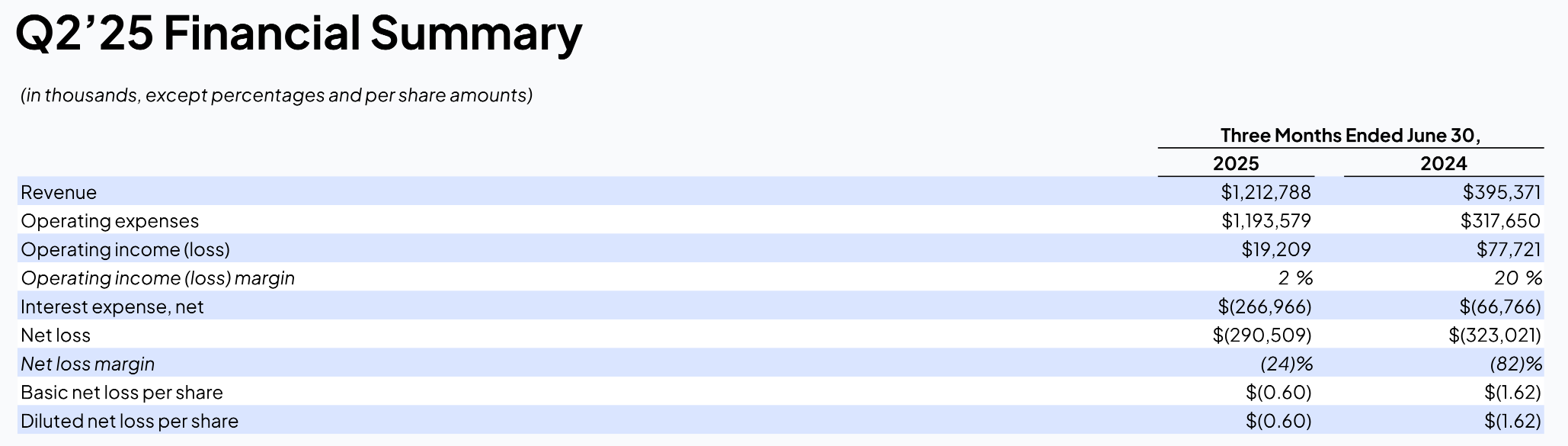

Q2 2025: $1.2 billion revenue; GAAP operating income $19.2 million (2% margin) and GAAP net loss $290.5 million.

Funding: $14.5+ billion total, mostly debt.

CapEx: $8.7 billion in 2024 (YTD $3.9 billion, $2.9 billion in Q2 2025 alone).

Interest expense: $349.2 million in 2024 (YTD $513.5 million) - it may exceed $2 billion/year.

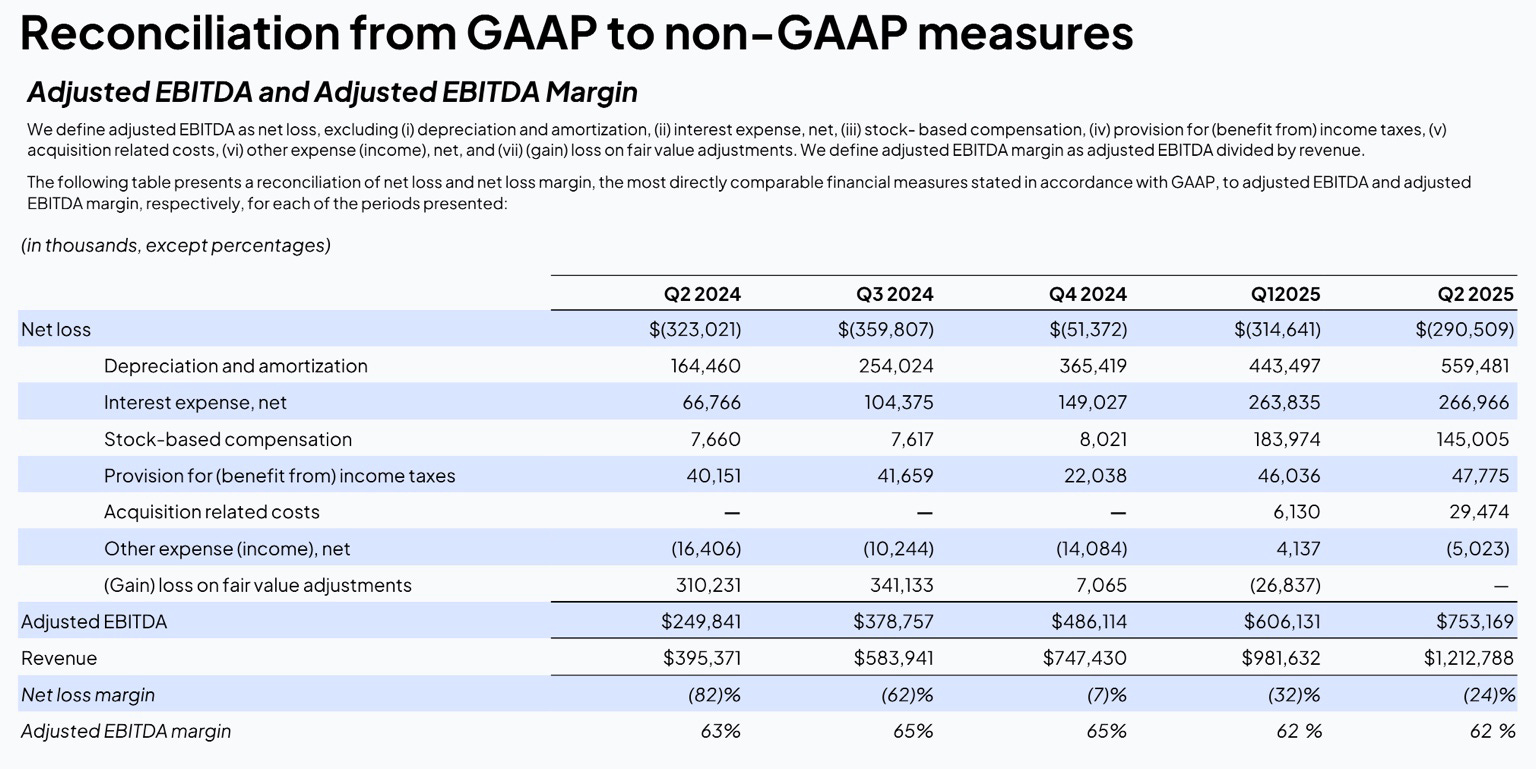

The company reported $1.2 billion in revenue in Q2 2025, with a $30 billion backlog. Yet, despite a 62% adjusted EBITDA margin, GAAP operating income was only $19.2 million (2% margin) and GAAP net loss was $290.5 million in the quarter.

The reconciliation explains why: The two items adjusted EBITDA ignores are huge - $559.5 million in depreciation & amortization (46% of revenue) and $267 million in interest (22% of revenue) and they’re not accounting quirks; you can’t ignore GPU decay or debt service and call it “profit”. Add $2.9 billion of Q2 2025 CapEx, and it’s obvious why EBITDA is the wrong yardstick for a CapEx-heavy, fast-obsoleting GPU fleet: with GPUs turning over every 3-4 years, depreciation is a recurring cost of staying competitive, not a non-cash nuisance. Treating adjusted EBITDA as earnings here is like valuing a steel mill while pretending the furnaces never wear out.

Concentration risk is rising, not falling. 62% of 2024 revenue came from Microsoft; another big slice appears to be NVIDIA renting back its own GPUs. In Q2 2025, Customer A (likely Microsoft) was 71% of revenue, with the next three customers (two of which are likely OpenAI and NVIDIA) each <10%.

Even with scale, profitability doesn’t show up. This isn’t the profile of a thriving, diversified platform. It’s a company built on sand, propped up by a couple hyperscaler clients and a debt-fueled, synthetic demand cycle.

Debt & Leverage: CoreWeave’s Debt-Fueled Growth Machine

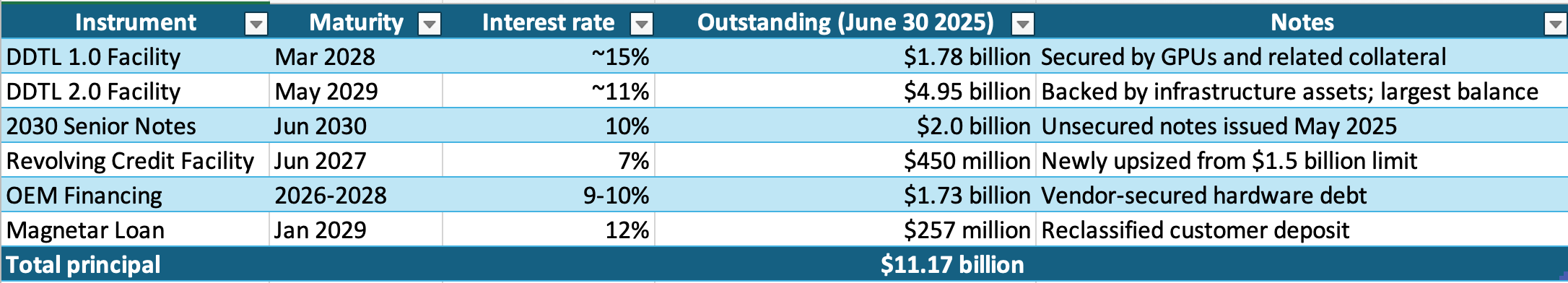

CoreWeave runs on borrowed money. By June 30, 2025, total debt had ballooned to $11.17 billion, up from $8 billion just six months earlier - excluding another $3.5 billion in lease liabilities. Most of this sits in high-interest, secured term-loan facilities tied to depreciating GPUs, so the very hardware generating revenue also underwrites rising leverage.

The bulk of CoreWeave’s financing comes from its Delayed-Draw Term Loan (DDTL) facilities - effectively large, asset-backed loans that can be tapped in stages to fund GPU purchases. DDTL 1.0, arranged in 2023 for up to $2.3 billion, carries a floating rate of roughly 15%, amortizes quarterly, and comes due with a balloon payment in March 2028. It is guaranteed by CoreWeave and secured by its subsidiaries’ assets, with strict prepayment penalties.

In May 2024, the company added DDTL 2.0, a much larger $7.6 billion facility with a variable interest rate averaging around 11%, determined by the credit quality of customer contracts backing each draw. By June 30, 2025, CoreWeave had drawn $4.95 billion and extended the draw window to September 2025. Repayments begin in January 2026, with each tranche maturing five years after funding.

In July 2025, CoreWeave introduced DDTL 3.0, a new $2.6 billion facility to finance infrastructure for a “strategic customer”. It’s priced at a floating benchmark plus 4%, includes a 0.5% annual fee on undrawn funds, begins amortizing in 2026, and matures in August 2030.

These DDTL loans are the engine of CoreWeave’s growth, but also its Achilles’ heel. They’re collateralized by GPUs whose market rental rates have already fallen 50-70%, shrinking collateral value just as repayment schedules begin referencing depreciated hardware. The company itself proudly highlighted this structure in its S-1 filing:

“Our recent raise of $7.6 billion in committed GPU infrastructure-backed debt […] represents one of the largest private debt financings in history […]”

The structure may sound sophisticated (secured, self-amortizing loans tied to specific customer contracts) but it’s fragile. In theory, each loan’s principal and interest are covered by customer cash flows during the contract term, supposedly producing “positive free cash flow”. In reality, the company is borrowing against assets that must be replaced every few years, so much of that “cash generation” is already committed to the next CapEx cycle. It’s less a flywheel than a treadmill - constant motion without real progress in cash generation.

Through the first half of 2025, CoreWeave paid $2.088 billion toward debt service - $1.575 billion in principal and $513.5 million in interest, while posting a $190 million operating cash flow loss.

With total debt up 40% in six months, climbing to $11.17 billion, and leverage above 70%2 of total capital, the balance sheet is running on financial momentum, not operating cash.

At an average borrowing cost near 11%, CoreWeave’s annualized interest bill now approaches $1.2 billion, or roughly $100 million/month, before factoring in new obligations such as the $2.6 billion DDTL 3.0 and $2 billion in 10% senior notes issued mid-2025. Including these, total monthly interest could soon exceed $120 million, depending on rate resets and drawdowns. Principal repayments add another $250-300 million/month, implying total monthly debt service of $350-420 million, far beyond what the business generates from operations.

As of mid-2025, cash and equivalents (including restricted) stood at $2.05 billion, with roughly $4 billion in remaining borrowing capacity, much of it fenced off by covenants, escrow requirements, and usage restrictions.

At its core, this is a high-debt, high-CapEx model built around a few hyperscaler clients and rapidly aging hardware. In perfect conditions - strong AI demand, easy credit, and cooperative lenders - it can function. But if demand softens, credit tightens, or a major customer hesitates, the same leverage that fuels CoreWeave’s expansion could quickly become its choke point. Until the company produces durable, positive operating cash flow, its debt looks less like growth capital, and more like a ticking constraint.

A Commodity Business Dressed as a Platform

CoreWeave rents GPUs by the hour, a commodity service with little differentiation. Unlike AWS, Azure, or GCP, which layer profitable software and services’ ecosystems atop their infrastructure, CoreWeave lacks a sticky developer platform, proprietary tools, or meaningful brand moat. Its only advantage is proximity to NVIDIA and preferential chip access, an edge that can erode quickly as others scale up. In a race to install the most GPUs and rent them out, price becomes the lever, margins compress, and the business drifts toward the bottom-line economics of a commodity.

The company presents this hourly rental and contract model as a proven, repeatable engine of growth, yet in reality, the company has only recently completed its first full 54-month lifecycle since pivoting from crypto mining to AI data center (2019-2020). The slides depict a mature, steady cash-flow machine - 3-month install, then monthly payments in months 6-30 and 30-54, with GPUs rolling into an on-demand pool afterward. With its AI-specific scale-up only starting in 2023, CoreWeave has barely two years of track record under this model.

At the Deutsche Bank 2025 Tech Conference on August 27, 2025, Nitin Agrawal, the company’s CFO reinforced this framing, saying CoreWeave still evaluates projects on a 2.5-year payback (on an adjusted EBITDA basis), consistent with the S-1 filing: secured, self-amortizing DDTL debt is tied to specific customer contracts and structured over five years, with the goal that interest and principal are covered during the contract term while throwing off positive free cash flow to the company.

That may be true on paper, but the economics still deserve scrutiny. A 2.5-year EBITDA payback is not a profit payback; it ignores depreciation/obsolescence and the fact that GPUs typically need replacing every 3-4 years. By the time a primary term ends, CoreWeave faces another large CapEx cycle just to stand still. And because the loans are collateralized by depreciating GPUs, the collateral base shrinks even as replacement spending looms. In short, the inflows during months 6-54 look less like durable profits and more like temporary cash returns in a perpetual replacement loop, one that depends heavily on a few large contracts to keep refinancing and rollout on track.

These structural weaknesses feed directly into NVIDIA’s ecosystem.

The NVIDIA Loop: How the GPU Giant Became the Engine of AI Infrastructure

NVIDIA has evolved beyond supplying GPUs to become a key architect and enabler of AI infrastructure. After acquiring Mellanox Technologies in 2020, NVIDIA expanded its networking and data center stack and has seen its Data Center segment become the biggest revenue and profit driver. In parallel, NVIDIA has invested in, or partnered with, AI data centers like CoreWeave, Nebius Group (NBIS 0.00%↑), and Lambda Labs structuring deals where the neoclouds borrow against long-term contracts with hyperscalers to purchase NVIDIA GPUs. In some cases, NVIDIA steps in as a safety valve, for example, an initial order to lease unsold compute capacity (e.g. a $6.3 billion agreement in September 2025 with CoreWeave). The loop amplifies GPU sales and installed base, but it also financializes demand: growth depends on credit markets, contract durability, and rapid hardware refresh cycles. CoreWeave, with 470MW active vs. 2.2GW contracted, still must finance vast expansion, mostly with debt collateralized by depreciating GPUs. It’s a fragile flywheel powered by leverage that can keep spinning only while credit and chip cycles cooperate.

Final Thoughts: Revenue Is Not Shareholder Value

The CoreWeave story captures both the promise and peril of the AI infrastructure boom. Behind the growth headlines lies a business model built on borrowed money, depreciating hardware, and a handful of customers. For now, debt and hype mask the fragility, but the economics eventually surface - they always do.

None of this means CoreWeave can’t succeed or that the AI build-out will stop. It means that level-headed investors should separate AI as a secular trend from the companies financing it. Leverage, concentration, and obsolescence make for a difficult mix even in expansionary cycles, and a dangerous one when liquidity tightens.

To borrow Jeff Bezos’s framing, AI’s trajectory resembles an industrial bubble: the technology’s promise is real, but the financing mechanisms around it are fragile. Like the fiber-optic boom that bankrupted its builders yet connected the modern internet, the AI buildout will likely leave behind lasting infrastructure - even if some current players don’t survive. That’s the paradox of industrial revolutions: society gains enduring assets, but many investors don’t.

As a value investor, I’m drawn to businesses that compound capital from within, not ones that must constantly borrow it. In CoreWeave’s case, the question isn’t whether demand for GPUs will grow, but whether the company can ever capture durable economics from it. Until it proves that with consistent operating cash flow and a self-funding model, the risks remain greater than the rewards.

S-1 filing is a document submitted to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) by a company planning to go public. It provides investors with detailed information about the company’s business model, financial statements, risks, management, and major shareholders. Essentially, it’s the company’s IPO prospectus, designed to help potential investors assess the business before its stock begins trading publicly.

Leverage (Debt-to-Total-Capital) is a measure of how much a company relies on debt versus equity to finance its assets. It’s calculated as debt ÷ (debt + equity). The higher the ratio, the more the company’s capital structure is funded by borrowed money rather than shareholders’ equity.

The debt collateralization risk you highlighted applies across the neocloud space, not just CoreWeave. When Nebius or others borrow against hyperscaler contracts secured by rapidly depreciating GPUs, they're essentialy betting that replacement cycles will be funded by new contracts before the collateral value erodes. The 2.5 year EBITDA payback looks impressive until you realize the hardware needs replacing in 3-4 years. This works beautifully in a capex boom but becomes a refinancing nightmare when credit tightens or demand softens.