Undervalued by Design: Amazon, Alphabet & the Economics of Aggregation

Pre-internet rules can't price post-internet platforms

The internet didn’t just change how companies sell - it rewired how markets settle. Pre-internet, industries drifted into regional oligopolies. Post-internet, distribution flattened, geography collapsed, and aggregators can scale to billions at near-zero marginal cost, compounding data and network effects as they grow. That’s why search consolidated into one engine, digital ads cluster with a few platforms, and cloud/e-commerce now feel like metered utilities.

Winner-take-most isn’t a slogan; it’s the operating system of modern markets.

These aggregators capture an outsized share of global profits and have driven index returns for a decade, despite being the most scrutinized businesses on Earth. In an efficient market, that shouldn’t keep happening. It does because market participants still price internet-era platforms with conventional pre-internet portfolio rules.

Why the Giants Stay Cheap

It sounds paradoxical: how can trillion-dollar companies like Amazon.com (AMZN 0.00%↑) and Alphabet (GOOGL 0.00%↑) be cheap? Because markets misprice aggregators. A 1940s “diversified fund” rule soft-caps single positions, forcing portfolio managers to trim winners as they compound. Active managers avoid “obvious” giants to look non-consensus, which helps justify fees, suppressing demand for aggregators. Only about a third of public-equity capital is earmarked growth, yet Amazon and Alphabet still behave like growth businesses; heavy reinvestment and scant dividends deter the other 70%. Finally, over-diversification leads investors to cut back outsized winners on principle even as profits concentrate. The result is a persistent supply–demand mismatch that keeps pockets of Big Tech cheap until maturity broadens the buyer base.

Aggregation Beats Regulation

Regulatory risk completes the picture: regulators can slow or reshape business models, even force organizational changes, but the economics of aggregation are hard to regulate away. Digital demand coalesces around the lowest-friction, most relevant platforms, so scrutiny usually slows earnings growth rather than breaking moats.

For example, in the September 2, 2025 ruling of DOJ v. Google, Judge Amit Mehta affirmed Google’s illegal search monopoly but imposed narrow remedies, no Chrome divestiture and default-payment deals (including Apple) can continue, while barring exclusivity and ordering Google to share parts of its index and aggregated user-interaction data with qualified rivals. He cited the rapid rise of generative AI chatbots (ChatGPT, Claude, and Perplexity) as emerging competitive pressure; Alphabet’s stock jumped 10% on the news - the moat bent, not broken.

When the Buyer Base Broadens

Together, these structural frictions keep pockets of Big Tech systematically undervalued, not a bug of market attention, but a feature of market structure.

As they mature, their valuation discounts shrink because they fit conservative mandates: Apple and Microsoft sit on the mature/less-undervalued side; Amazon remains earlier/more undervalued, with Alphabet and Meta mid-cycle.

What widens the pool of eligible buyers? Capital efficiency, steady and rising earnings, dividends, low core volatility, and limited moonshot spend. Buybacks accelerate the re-rating by soaking up supply and letting pessimists exit, lifting per-share economics over time; Apple’s share buyback program is the playbook.

Alphabet (Google): Execution Over Hype

Alphabet keeps being underestimated precisely because it communicates like an engineer, not a hype machine.

Core engines that refuse to slow: Search and YouTube remain two of the world’s largest ad funnels. Google Cloud Platform (GCP) is an increasingly credible number 3 in the hyperscalers arena with improving unit economics.

AI execution > AI narrative: When third-party leaderboards and blind user tests swing toward Google Gemini, the stock rarely re-rates the way the headlines do. That credibility lag is a recurring opportunity for level-headed investors.

Autonomy is real option value: Waymo (robotaxis) has been scaling paid rides across multiple cities and partnering with existing networks. Whether Autonomous Vehicles (AV) disrupts ride-hailing or plugs into it, Alphabet owns a leading asset that the market still prices as a sideshow.

Why does it stay cheap? Regulators are a permanent headline; and the company conscientiously under-celebrates moonshot optionality. For level-headed investors, that lack of drama is the feature, not the bug.

What could narrow the valuation gap? Easing regulatory overhang (see Sept 2, 2025), durable Cloud margin expansion, crisper Other Bets disclosures, and continued strength in Search/YouTube.

Amazon: Option Value Over Optics

Amazon isn’t a retailer. It’s an ecosystem of compounding flywheels, many physical, most misunderstood. If you were designing a large-cap to stay undervalued while compounding intrinsic value, you’d copy Amazon’s playbook:

Accounting optics mask true earnings power: Heavy reinvestment (TTM CapEx: $108B) keeps reported profits optically small and volatile relative to long-run potential.

No dividend, minimal buybacks: That excludes swaths of conservative buyers and removes the bid that share buybacks provide when shareholders need to trim for non-fundamental reasons.

Moonshot opacity: Little disclosure on big bets (e.g. Project Kuiper) turns uncertainty into a price multiple penalty.

Incremental share supply: Employees’ compensation mix (TTM Stock-Based Compensation: $20.5B) and founder-level selling add to float over time.

Yet, its prime assets widen its moats:

Amazon Web Services (AWS), born in Amazon’s retail trenches, remains the internet’s enterprise utility, think electricity, but for computing. Instead of companies buying lots of servers upfront (CapEx) and hoping they guessed future demand, AWS lets them rent what they need by the minute (OpEx) and scale up or down instantly. Example: a retailer might need 100 servers on Black Friday but only 10 the rest of the year; with AWS, they spin up 100 for the weekend and shut them off after. This “pay-as-you-go” model kills capacity guesswork, cuts waste, and lets engineers focus on building apps rather than babysitting hardware. Over time, customers adopt more AWS services (databases, analytics, AI), which makes workloads stickier and the platform even more like a must-have utility. While Azure and GCP can gain market share, AWS still “taxes” vast swaths of online activity, with a long runway in AI workloads and margin leverage. Behind the software lies Amazon’s hardest-to-clone moat: fulfillment nodes, middle-mile, last-mile, robotics, data centers, and power, because source code is copyable; concrete and gigawatts aren’t.

Commerce has evolved from a bookstore to a marketplace: In the old 1P1 model, Amazon bought inventory and resold it; in the 3P2 model, independent sellers list products while Amazon supplies traffic, tools, and logistics. Shifting toward 3P lowers Amazon’s inventory risk, boosts margins, and scales faster. This creates a two-sided network: more shoppers attract more sellers, and more selection; selection plus fast shipping (same-/next-day) makes customers start their search on Amazon out of habit. Commerce search queries have purchase intent baked in. That’s why ads scaled from rounding error to tens of billions of high-margin revenue. Sellers pay to promote products; those ad dollars help fund cheaper, faster delivery and better tools - drawing in more shoppers, which makes ads more valuable. Meanwhile, Amazon earns a “toll” on every order: a retail margin on 1P, and on 3P a referral fee (often 8-15%, and higher for select categories) plus optional services like Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) and ads. Stack these and Amazon’s share of a 3P sale, its take rate, rises (e.g. a $100 sale might yield $25-30 in combined fees/services). Crucially, heavy investment in warehouses, robots, trucks, and data centers isn’t vanity; it increases speed, which lifts conversion, which attracts more sellers and ad spend. That’s why commerce + ads acts like a self-reinforcing flywheel with expanding profit margins.

AI everywhere amplifies the whole machine: Amazon Bedrock and Amazon Q in the cloud stack; seller and shopper copilots; summarization of customer reviews; dynamic cataloging; and healthcare experiments (e.g. a vetted Health AI assistant). Alexa is being re-platformed with generative AI capabilities. These are thousands of tiny ROIs (Return on Investment) that rarely show up in a single quarter but reshape five-year unit economics.

Why does it stay cheap? The company optimizes for option value over optics. Until Amazon behaves more like a “mature” cash-returner, the broadest buyer base will remain underweight. I would rather see Amazon continue its strategy of reinvesting heavily now to cash in for decades to come.

What could narrow the valuation gap? A visible step-up in AWS margins, steadier commerce EBIT, clearer reporting on moonshot projects, and, eventually, a persistent buyback program that absorbs structurally motivated sellers. Amazon doesn’t need to change its DNA; it only needs to let compounding become visible.

The “Law of Large Numbers” Myth

Big doesn’t mean done. Even the largest companies can keep compounding when:

There’s still a lot left to win: Amazon’s e-commerce is still a minority of total retail. Alphabet benefits from a secular trend of ad budget shifting from linear TV and radio to Search and YouTube.

Mix keeps getting richer: Amazon tilts to the higher-margin marketplace (3P), ads, Prime, and AWS; Alphabet compounds Search/YouTube and scales Cloud + subscriptions (e.g. YouTube Premium, Google One).

New growth engines are incubating: Amazon’s Project Kuiper (low-Earth-orbit satellites) can power AWS, and add a new business line; Alphabet’s Waymo and AI models/agents (Gemini) can unlock fresh revenue streams alongside the core.

The bottom line is that optionality (credible new bets) is an asset. Markets often treat it as a headache in the short term as heavy investment cycles compress cash flows, but patient level-headed investors benefit when those options start paying off.

How I Build My Portfolio in The Aggregation Age

My biggest risk isn’t volatility; it’s permanent capital loss, to borrow Buffett’s framing. A close second is opportunity cost: missing the compounding of a few dominant platforms. So I’ve built my portfolio around a simple playbook:

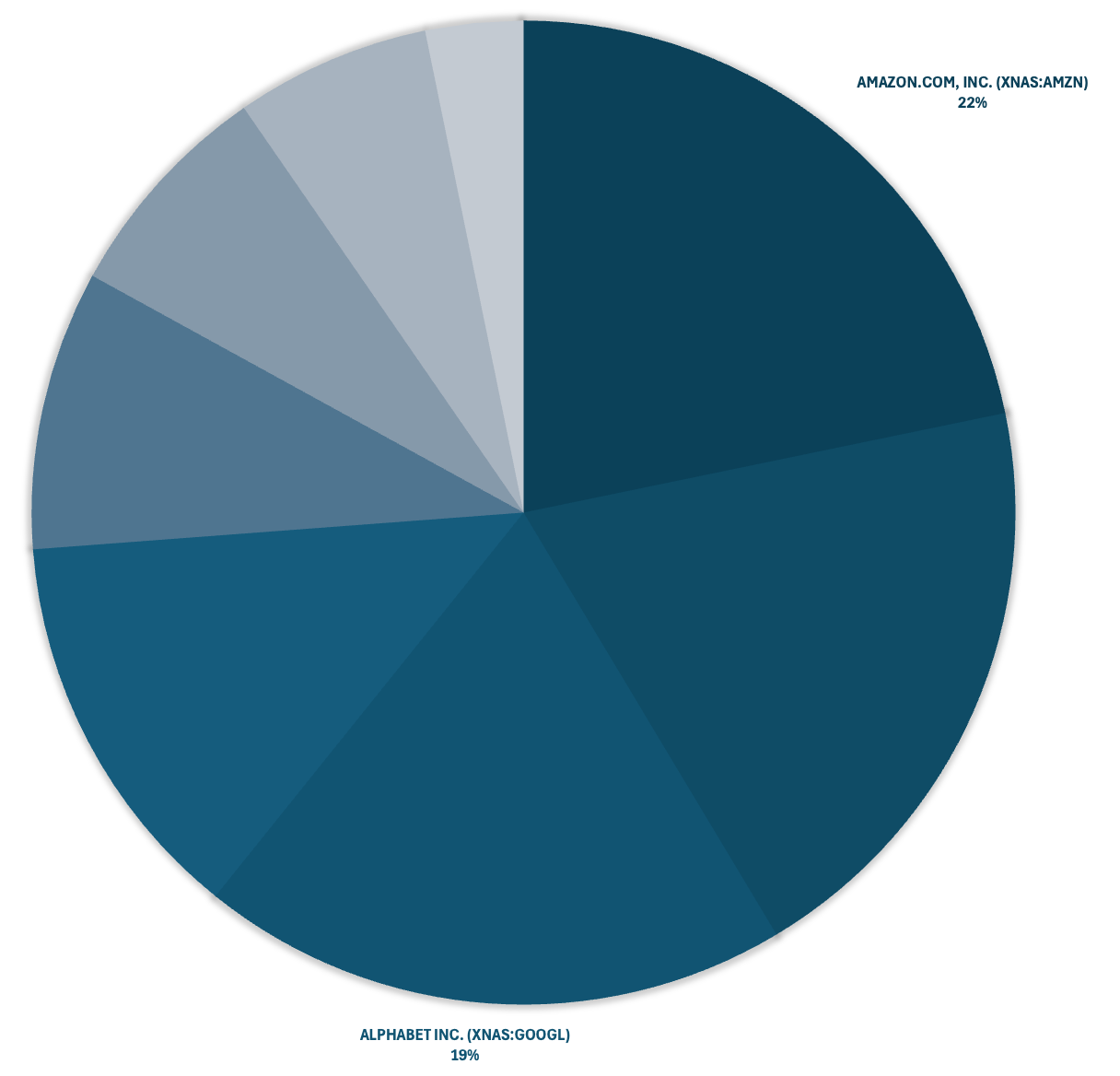

Diversify by business model, not by ticker: Through Amazon and Alphabet, I spread exposure across search, cloud, ads, commerce, AI, and devices. Mercado Libre (MELI 0.00%↑) and Pinduoduo (PDD 0.00%↑) deepen my exposure to commerce and ads while adding growth from Latin America and China; they also bring leading fintech rails in LatAm (Mercado Pago & Mercado Crédito) and, in Pinduoduo’s case, a scaled agriculture marketplace connecting farmers to consumers. Brookfield Corporation (BN 0.00%↑) adds weight in real assets: physical infrastructure, real estate, energy, asset management, and insurance. The result is business-model diversification, even if it means owning only a handful of businesses.

Concentrate where economics concentrate: If one or two companies truly aggregate a market and drive sustained growth, being underweight them is the real risk.

Use a core/option structure: I hold core positions in dominant platforms, and keep smaller positions in emerging aggregators or leaders in niche markets. I trim or sell out of positions only when the investment thesis weakens or when I identify a better opportunity, not because a line item looks too big.

Focus on unit economics and long runway: I prefer businesses that can reinvest at high ROIC (Return on Invested Capital) with strong moats and great unit economics, over stocks that look optically cheap, but lack durability.

This is my portfolio construction and part of my investment philosophy. It fits my goals and risk tolerance; it’s not a recommendation for anyone else.

Final Thoughts

Markets still price digital moats with analog rules. In today’s economy, scale lowers risk and deepens moats - the old playbook flips. My edge is simple: own the obvious winners when portfolio norms keep others underweight. For me, that means staying long Amazon and Alphabet, patiently, on purpose.

Amazon 1P (“first-party”): Amazon buys inventory wholesale from brands and distributors and resells to customers. Revenue is booked gross; Amazon sets price and bears inventory/markdown/logistics risk. 1P is often used to seed selection, guarantee availability, and keep headline prices competitive, typically at lower margins than marketplace services.

Amazon 3P (“third-party marketplace”): Independent sellers list products on Amazon; Amazon earns service fees (referral %, closing fees), optional FBA fees (storage, pick/pack/ship, customer service), and ads revenue, while the seller keeps product margin and bears inventory risk. Revenue is booked net (as services). 3P generally delivers higher return on capital and scales faster for Amazon. Effective take rate can vary widely by category, fulfillment method, and ad spend.