Lifestyle Inflation Trap: The Upgrade-to-Obligation Pipeline

A behavioral map of how lifestyle upgrades become fixed costs, and the guardrails that protect slack

Lifestyle inflation is about upgrades that turn into fixed monthly commitments. The key variable is slack - what’s left after fixed costs. Slack gets squeezed from three directions: cost-of-living squeeze (housing, childcare, essentials), lifestyle creep, and fixed-cost creep. As slack shrinks, budgets get less forgiving: a bigger share of income is pre-committed before you even make choices. The rest of this article explains the psychology behind the trap and the guardrails I use to keep pay raises from turning into permanent obligations.

Since 2009, my income has nearly quadrupled, and the main reason my spending didn’t mechanically follow is that I tracked it closely and put guardrails in place early. My fixed costs still rose with family life and later fell again, while I lived below my means and tried to keep upgrades reversible and avoid letting new “defaults” turn into permanent monthly bills. That personal experiment is the lens for what follows.

I focus on Italy (where I live), the UK (where I spent 13 years), and the US (where most of my portfolio exposure sits) because they’re familiar to me and because they represent three different mixes of wages, housing costs, welfare support, and consumer credit that shape how easily spending turns into fixed commitments.

This isn’t a moral judgment - plenty of households are constrained by housing, childcare, and wage stagnation, with fixed costs leaving little room to save. This article focuses on what happens when surplus exists and quietly turns into recurring commitments. Next, I’ll define the key terms and lay out a simple dashboard to spot where slack is leaking.

The Slack Framework (Definitions + Indicators)

Slack is the income left after fixed costs - your “margin”. It’s what lets you absorb surprises, save, invest, and make decisions without panic.

Why slack matters: Saving is the buffer that prevents ordinary problems from becoming financial emergencies. A cash reserve turns a car repair, medical bill, or job gap into a manageable setback, instead of a debt spiral. Investing comes after that foundation. Once an emergency buffer exists, investing is what you do with surplus slack so it can outpace price inflation1 and compound2 over time.

Lifestyle inflation (or lifestyle creep) is what happens when rising income turns into higher “defaults”, especially fixed monthly commitments, so your lifestyle expands without you explicitly choosing it.

The “Big Three” are the high-impact categories where upgrades most often become sticky: housing, transportation, and education/childcare.

Fixed-cost creep is the slower leak: subscriptions, app add-ons, device financing, installments, premium tiers - small recurring payments that compound into a meaningful monthly drain.

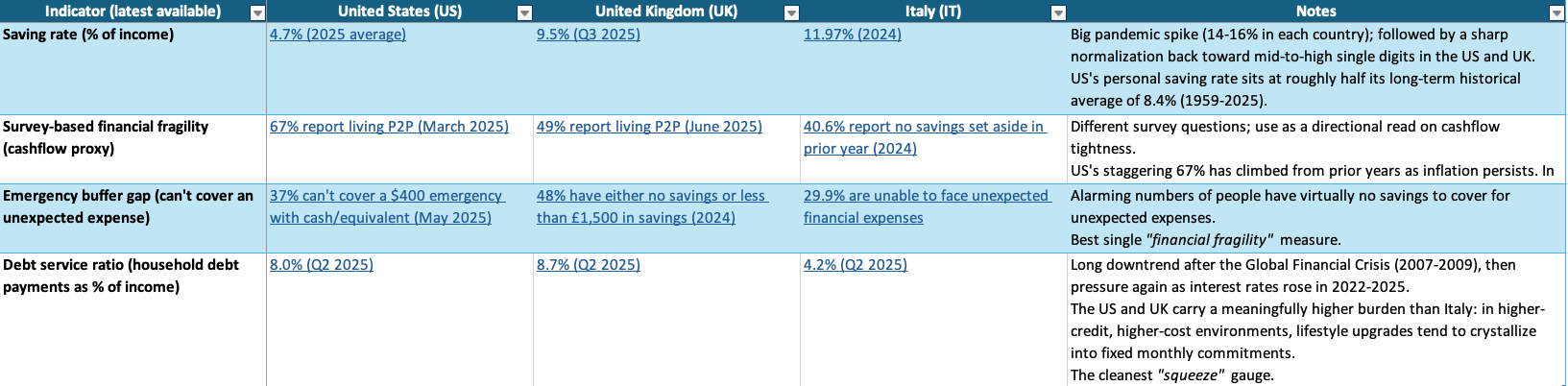

Because slack isn’t reported directly in national statistics, I use a small dashboard of indicators as proxies for household financial fragility. When saving rates3 are low, it suggests less income is being retained as an emergency buffer. When more people report living paycheck-to-paycheck4, it signals tighter month-to-month cash flow. When emergency buffer gaps are large, it implies many households can’t absorb a routine shock without borrowing. Finally, the Debt Service Ratio (DSR)5 shows how much income is pre-committed to lenders (often the downstream result of upgrades that became contractual obligations), before groceries, rent, childcare, or savings.

Definitions differ across sources (macro accounts, central banks, surveys); levels are indicative. The point is direction and pressure (slack), not precise cross-country ranking.

Together, the indicators explain why lifestyle creep is easy to fall into: as prices rise and credit stays available, spending can become structural. Price inflation also resets what “normal” costs, and people adapt quickly - so the baseline drifts upward even without deliberate upgrades.

Where the Trap Springs: The “Big Three” + Fixed-Cost Creep

Financial behavior across Italy, the US, and the UK isn’t just about “discipline” or personal choices; it’s shaped by slack, what’s left after fixed costs. Over the past two decades, slack has narrowed for many younger households and for the “squeezed” middle class as housing and other essentials take a larger bite. But when surplus does exist, the trap usually isn’t daily coffee. It’s the conversion of liquid cash into sticky, high-status commitments: the “Big Three”.

The “Big Three” are the headline drivers because they’re identity-linked and hard to downgrade. Housing upgrades (a larger mortgage or pricier neighborhood), cars/transport upgrades (buying or leasing high-end vehicles that signal status but depreciate rapidly), and education/childcare upgrades (after-school, tutoring, private schooling, premium extra-curricular) don’t just raise spending, they harden it into fixed monthly outflows. This is where cost-of-living “squeeze” (rising rents, bills, essentials) ends and lifestyle creep begins: voluntary upgrades that become the new baseline. For high earners in particular, these categories inflate disproportionately because they’re tied to identity and status - once you upgrade your zip code, car, or schooling choices, downgrading can feel like a loss of social standing, turning what was once a luxury into a permanent cost.

There’s also a quieter form of lifestyle creep that rarely feels like “spending”: fixed-cost creep. Modern consumption increasingly arrives as a bundle of recurring payments - subscriptions (streaming, cloud storage, gyms), app add-ons, device financing, and “Buy Now, Pay Later” (BNPL)6/installment plans that turn discretionary wants into recurring obligations. Each one is small and easy to justify in isolation (“it’s only $15/month”), but together they compress slack the same way a bigger mortgage does: they pre-commit tomorrow’s income before you’ve even made choices about saving, investing, or experiences. And because these costs are fragmented and often auto-billed, they’re easy to ignore - until a shock hits, or your income dips and you discover how little room you actually have.

A simple way to see it: $15/month doesn’t feel like much, until it’s 12 different subscriptions ($180/month, $2,160/year). Add a couple of 0% installments (phone, laptop, furniture) and a lease upgrade, and you’ve built a stealth mortgage: a stack of contractual monthly outflows that behaves like fixed costs, even though it started as optional.

This is where lifestyle inflation really happens - not in one big splurge, but in commitments that quietly turn your future slack into someone else’s recurring revenue.

The Hedonic Treadmill: Why More Becomes the New Normal

One of the strongest drivers of lifestyle creep is the hedonic treadmill (hedonic adaptation): we quickly get used to improvements (a pay raise, a new car, a bigger house) and drift back toward a baseline level of happiness. What starts as a treat becomes “normal”, expectations rise, and you start chasing the next upgrade just to get the same buzz.

Lifestyle creep is the treadmill playing out in your budget: higher earnings fuel higher “defaults”, and the real trap isn’t the upgrade itself, it’s when the upgrade becomes a recurring bill. The pleasure fades, but the bill stays, shrinking slack month after month. This is how higher income turns into higher defaults: adaptation pushes you to upgrade, and credit makes it easy to lock the upgrade into monthly payments, reducing slack.

The practical takeaway is simple: if you let temporary treats become permanent obligations, your “normal” gets more expensive faster than your freedom grows. Even if the boost fades within weeks or months, the higher fixed costs remain - consistent with adaptation findings since the classic 1978 study and later work pointing in the same direction.

The Dopamine Loop: How Wanting Becomes a Monthly Bill

The biological engine of the hedonic treadmill is dopamine. Neuroscience separates “wanting” (craving/anticipation) from “liking” (actual enjoyment). When you want a new purchase, dopamine fuels anticipation; after you buy it, that spike fades, the item becomes the new “normal”, and the brain starts looking for the next hit. Marketing and social feeds exploit this loop by constantly resetting what a “good life” looks like, so lifestyle creep can feel automatic: your brain rewards pursuit more than possession.

A second force is present bias (hyperbolic discounting): we discount the future steeply, so immediate rewards feel disproportionately valuable. That’s why a smaller reward now can feel “worth more” than a larger reward later. In practice, this nudges people toward upgrades today and saving (and investing, if you do it) later, until the upgrade hardens into a fixed monthly commitment and slack quietly shrinks.

I can’t turn these instincts off, so I try to design around them. I steer discretionary spending toward experiences (travel, meals out) rather than possessions, because experiences become memories and part of your life story and identity while objects fade into the background - consistent with consumer-psychology evidence that doing tends to outlast having. As my income rose, I worked to keep luxuries optional rather than default, and I automatically route a meaningful share of raises/bonuses into investments before my baseline adjusts, so the default outcome of a raise isn’t a new recurring bill.

Final Thoughts

Lifestyle inflation rarely arrives as one big splurge. It arrives as “defaults”: upgrades that become fixed monthly commitments and quietly convert future slack into recurring bills. If you take nothing else from this, take the mechanism seriously - once a cost becomes contractual, it stops being a choice and starts acting like a tax on every future paycheck. I’m aware this lands differently depending on your starting point: if you’re squeezed, the goal is survival and stability (protecting slack and avoiding debt); if you have surplus, the goal is discipline, so pay raises don’t quietly harden into permanent commitments.

What’s helped me is treating slack like an asset to protect, not leftover cash to spend. My personal guardrails:

Capture raises automatically (“pay myself first”) - when income jumps, I immediately increase the amount that’s auto-routed to my investing account. I treat it like a bill I owe my future self, so the raise gets captured before my spending baseline resets.

Audit the “Big Three”: as my income grew, I deliberately kept housing from expanding with it - so the share of my income going to rent (early years) and then a mortgage (recent years) fell from 47% in 2009 to 21% on average over the past five years. The goal isn’t austerity; it’s avoiding permanent commitments that shrink slack.

Add friction to impulse buys: I use a 24-hour rule for non-essentials, avoid one-click checkout, and run a quick “cool-off” period before purchasing.

Prefer experiences and relationships over status (for readers with surplus slack, not for households in financial fragility): I’m happy spending on travel and meals out (especially when shared with people I care about), rather than purchases meant to signal status. As my income grew, I increased travel/experience spending from 6.2% of my income (2009-2013) to 14% (2021-2025).

If you want one practical starting point, measure the two places slack leaks fastest, and make the measurement a habit. First, compute your “Big Three” as a share of income and track it monthly for a year. Second, list every recurring payment (subscriptions, app add-ons, BNPL/installments, device financing), sum them, and annualize the total. This is the real value of tracking expenses and budgeting: not micromanaging every coffee, but making the invisible visible so “stealth fixed costs” don’t quietly become your new baseline. Seeing the one-line yearly number is often the fastest way to spot what you stopped noticing.

Price inflation is the sustained increase in the general level of prices for goods and services over time, which reduces the purchasing power of money (each euro/pound/dollar buys less).

Compound (compounding): the process where returns earn returns - your investment grows not only on the original amount, but also on past gains (e.g. capital appreciation, reinvested dividends).

Saving rate: the share of (after-tax) income that households set aside as savings rather than spending during a given period, typically expressed as a percentage (often calculated as personal saving / personal income).

Living paycheck-to-paycheck (P2P) means a household uses 90%+ of each pay period’s (after-tax) income to cover current expenses, leaving little or no money for savings or emergencies, so a missed paycheck or unexpected bill would create financial stress.

Debt Service Ratio (DSR): the share of household income used to make required debt payments (principal + interest) on loans like mortgages, credit cards, and auto loans - typically expressed as a percentage of income.

Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) is a short-term credit option that lets you split a purchase into multiple payments (often marketed as 0% or low-interest), typically paid in a fixed schedule (e.g. 4 installments), with fees or interest if you miss payments or extend the term.