Culture of Consumerism: The Default Is Spend

Why Western economies nudge consumption, and how to build a personal counterculture

In Western economies, spending isn’t just a personal choice; it’s a cultural default. Advertising keeps dissatisfaction on a drip feed, credit turns desires into monthly obligations, and social media widens your reference group from “people you know” to “people you follow”. If you treat this as a willpower problem, the current wins. The better framing is environmental: protect slack by building a cultural firewall between you and the forces trying to normalize “more, newer, better”.

Culture is the backdrop to this series. The Lifestyle Inflation Trap mapped the mechanism (upgrades → fixed bills → slack shrinks). The Demographics of Slack and Saving showed who even has margin to protect. And Why Saving Is Hard explained the wiring: why immediate rewards, status cues, and emotional relief make spending feel vivid while saving stays abstract. This piece adds the missing layer: the cultural engine underneath it all.

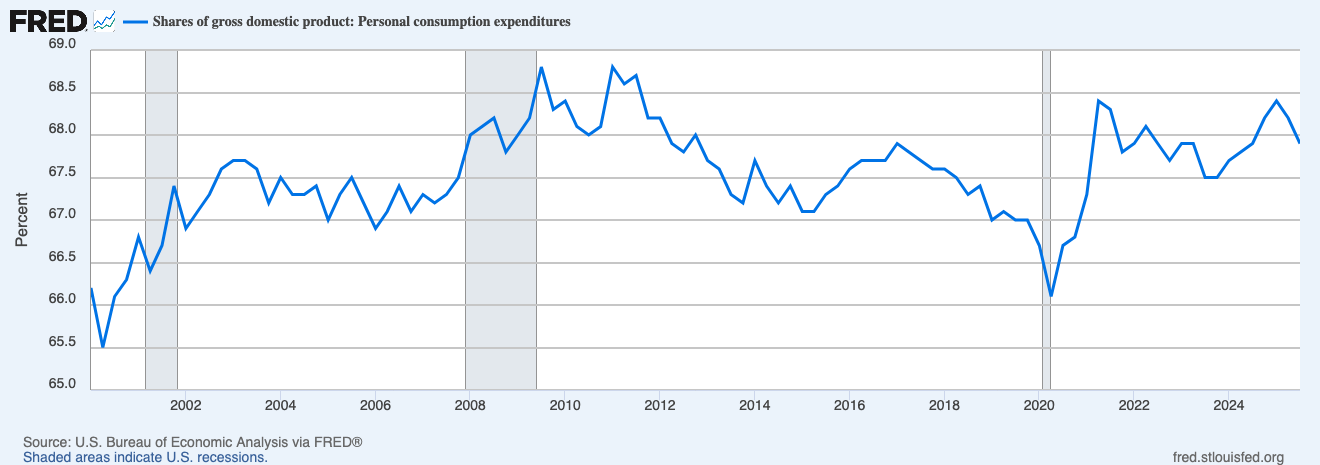

Western economies run on a kind of hedonic treadmill at the societal level. New products and trends constantly reframe “good enough” as “outdated”: last year’s phone works perfectly well, but the norm moves on; last season’s clothes still fit, but fashion cycles redefine what feels current. That churn isn’t accidental. It keeps demand alive and businesses profitable - because in many economies, consumption is a major driver of GDP. In the US, consumer spending is over two-thirds of GDP, so aggregate growth is heavily tied to households continuing to buy.

When consumption is structurally central to economic performance, you should expect a constant cultural tailwind behind “buy now”.

A simple framing I use: cultural slack is the distance between what your environment pushes you to spend, and what you choose to spend. When cultural slack is low, you need systems and boundaries.

The Western Consumption Machine: “More, Newer, Better”

Post-WWII America didn’t just get richer, it built an identity around mass consumption. In the 1950s, consumer spending was explicitly framed as civic participation: buying was cast as “good citizenship” in a mass-consumption economy. This is one reason the US is often the clearest expression of modern consumer culture: material upgrading became socially legible proof that you were “doing well”, and the suburban/home/car lifestyle became a central script.

This script spread beyond the US. As consumer society matured across industrialized economies, it was supported not only by rising incomes but also by public policy choices and resource abundance that made consumerist lifestyles scalable.

Advertising is not a sideshow in that system. Total advertising has been estimated at 1.3%-2% of US GDP over long periods, which is another way of saying: a meaningful share of the economy is dedicated to influencing attention, preference, and purchase.

If the default cultural message is “upgrade” you should assume your baseline will drift upward unless you build counter-defaults.

Easy Credit: Turning Wants Into Obligations

Consumer culture becomes far more powerful when it’s lubricated by credit. Modern card systems and general-purpose charge cards expanded in the second half of the 20th century; Diners Club (1950) is commonly cited as the first modern general-purpose charge card, and card-based payment systems then scaled quickly.

Credit matters culturally because it breaks the natural boundary between desire and affordability. Credit cards, installment plans, device financing, and BNPL lower the felt cost at the moment of purchase, so you experience the benefit now and push the pain into the future. That’s not just a personal weakness; it’s a product design feature in many consumer markets.

Culture supplies the urge; credit supplies the mechanism that turns urges into defaults. When financing is normal, you don’t need slack to upgrade; you need a monthly payment. That’s how lifestyle creep becomes fixed-cost creep: not one splurge, but the contractualization of your preferences into recurring obligations.

Credit doesn’t just increase consumption; it increases pre-commitment. Future slack gets sold forward.

Social Media: The Comparison Engine Goes Global

Social comparison is old. Social media industrialized it.

Western consumer culture existed long before Facebook, Instagram and TikTok - what changed is visibility. Social platforms compress comparison into daily life and shift spending from a mostly private choice to a public signal. The behavioral channel is well studied: people compare upward, feel the gap, and then try to close it; sometimes with purchases.

A consistent finding in recent research is that exposure to influencer content and curated consumption increases social comparison and “fear of missing out” (FOMO), and that these mechanisms can predict conspicuous consumption. More broadly, research on social media use links platforms to intensified social comparison and envy dynamics.

This matters because it shifts “normal” from your local peers to an algorithmically curated reference group. If your feed is full of upgraded kitchens, business-class flights, and luxury meals, the baseline quietly moves - even if your income doesn’t.

In other words, social media compresses cultural slack by raising perceived norms faster than real income grows.

Italy: “La Dolce Vita” Meets a Money-Taboo Hangover

Italy is a hybrid case: a cultural bias toward pleasure and presentation (food, social life, style), alongside an older tradition of prudence shaped by scarcity and post-war memory. You can see the tension in real life: “enjoy life” spending coexists with a quiet reluctance to be overtly ostentatious, depending on region, cohort, and context.

Where it gets financially tricky is that while the culture is openly pro-pleasure, family norms are less open about explicit planning. This is reflected in the fact that 40% of Italians aged 18-34 never discuss money at home and feel uncomfortable talking about finances. This discomfort is often linked to a traditional Catholic/Latin context where money talk can be seen as taboo or “greedy”, a sentiment echoed by Giovanna Paladino (Director of the Italian Museum of Saving), who argues that money is frequently viewed with suspicion even though it is fundamentally a tool for achieving life goals.

When consumer culture rises but money skills and money conversation lag, slack leaks faster, because the environment sells upgrades, while the culture doesn’t reliably teach planning.

The UK: Cautious Identity, Credit Reality

The UK sits between American-style consumer finance and a legacy of European caution. There’s still a cultural memory of restraint, but modern households face a high-cost baseline (especially housing) and frequent “just finance it” offers. One way to see the earlier “leverage era” is household debt: UK household debt as a share of income rose sharply from the late 1990s and peaked around 2008.

That history helps explain why the national conversation has shifted toward resilience, savings buffers, and vulnerability under cost-of-living shocks. The FCA’s Financial Lives work repeatedly highlights low emergency buffers for large segments of the population (for example, around one in ten adults with no cash savings, and many more with limited emergency reserves).

Guardrails That Work In a Consumer Culture

I assume the environment is optimized to push spending and normalize upgrades, so I rely on guardrails that reduce exposure, set boundaries early, and keep my baseline from creeping up by default. These are the practices I use to protect slack and preserve financial flexibility in a world that’s constantly asking me to spend a little more:

Be explicit and refuse the scoreboard: I’m explicit about what I’m willing to spend on because it genuinely improves my life (traveling, experiences with people I care about, learning), and what I refuse to treat as a scoreboard (branded goods, luxury signaling, status upgrades).

Social media and advertising hygiene: I rarely swipe on social media; when I do, it’s mainly to keep up with close friends I already speak to in real life. I follow a few finance-related, tech-focused profiles and other interests, but I don’t use social media as a lifestyle feed. Once a year, I do a spring cleaning of who I follow on Facebook and Instagram. In parallel, I treat advertising as background pressure: I unsubscribe from retail and promo e-mails, turn off marketing notifications, use ad-blocking where practical, default to a privacy browser on mobile, and avoid browsing that’s really just “shopping for a feeling”.

I don’t finance wants: I treat credit as a payment tool and safety tool, not a way to afford upgrades. I don’t put purchases on installment plans or BNPL. If I wouldn’t pay in full today, I assume I can’t afford the upgrade, and I pass.

Make money talk normal and useful at home: I talk about money openly with my family and friends. There’s no taboo; I keep it relevant to my life and focus on principles rather than numbers - budgeting, saving, investing, long-term planning, and the trade-offs behind choices. The goal is to learn from each other and build financial discipline as a shared language, so good decisions don’t depend on secrecy or last-minute stress.

Final Thoughts

Consumer culture sets the default, and the default is spend. In economies where consumer spending is structurally central, and advertising, credit, and social comparison are always on, the upgrade-to-obligation pipeline isn’t a personal moral failure, it’s the path of least resistance.

The way out is to build a small counterculture around yourself. Decide what “enough” looks like, control what gets your attention, refuse to finance upgrades into obligations, and lock in surplus before it gets absorbed by a higher baseline. That’s how slack stops being an accident and becomes something you protect on purpose. Once slack is protected, everything else gets easier: shocks stay small, choices stay flexible, and “living well” stops depending on keeping up.